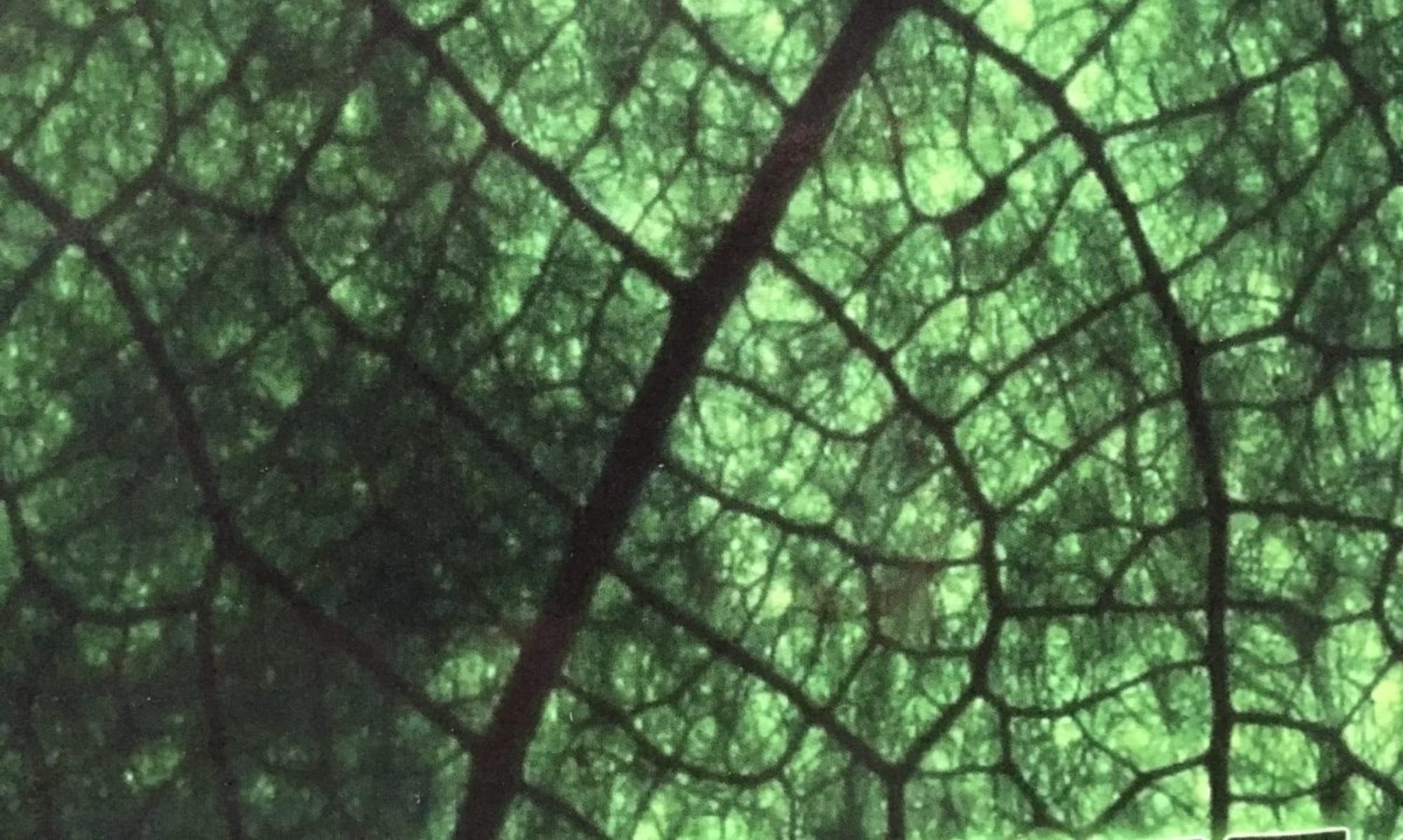

The vine has pretty, morning-glory-like flowers, but it is not native to here, and it climbs and grows everywhere. Literally this vine would cover every other plant, tree, and bush if I would let it.

I’m sure many gardeners hate this vine. But, in permaculture design class, we learn that everything serves a function in the ecosystem, and we can find uses for it. In keeping with that principle, I just cut the vine back rather than try to eradicate it. I use the cut foliage as free “chop and drop” mulch. Also, during the most punishingly hot time of year, I will often let the vine grow over most everything, as I figure it provides some shade to the soil and to roots of other plants.

The vine dies back in winter, doesn’t like even our mild winters.

One characteristic of this vine is that its stems get tough, ropy, almost woody. Maybe in some other times and places they have been used for rope — whether braided or single-strand. I thought of that the other day as I was cussing out some dried tangled strands of the vine that were intertwined with a nice pile of twigs and leaves that I was trying to grab from a neighbor’s curbside discard pile in order to add to my mulch pile.

It’s always good to remind myself that everything has its own inherent value. I can choose to remember that, or only choose to focus on the “pesky” characteristics of a thing.

Maybe I should do some weaving or rope-making experiments!

Speaking of natural rope, my friend Barbara, who is a longtime resident of Japan (maybe even a citizen), does a lot of writing and translation about traditional Japanese building methods, which rely entirely on locally grown wood, vines, and other materials. Thatched roofing and so on. Her Facebook posts are lovely. Here’s an excerpt from a recent one:

By now the old roof had been completely removed and the thatchers were repairing the roof frame. In addition to the rice-straw rope that had been used as binding on all the sites I’d visited previously, they were using another type of binding called “neso.”

“Neso” is obtained from “mansaku,” a kind of hazel that grows in the mountains of Gokayama. This should be used immediately after harvesting, while it is still green, but here they were forced to use branches that had been cut in November and had dried too much. Before using, the branches were soaked in water and then pounded to make them somewhat pliant. Even at best, this material is difficult to handle, but once the knot dries it becomes extremely hard and strong.

Barbara’s post is set to Public, and you can go here to read the full text and see photos.